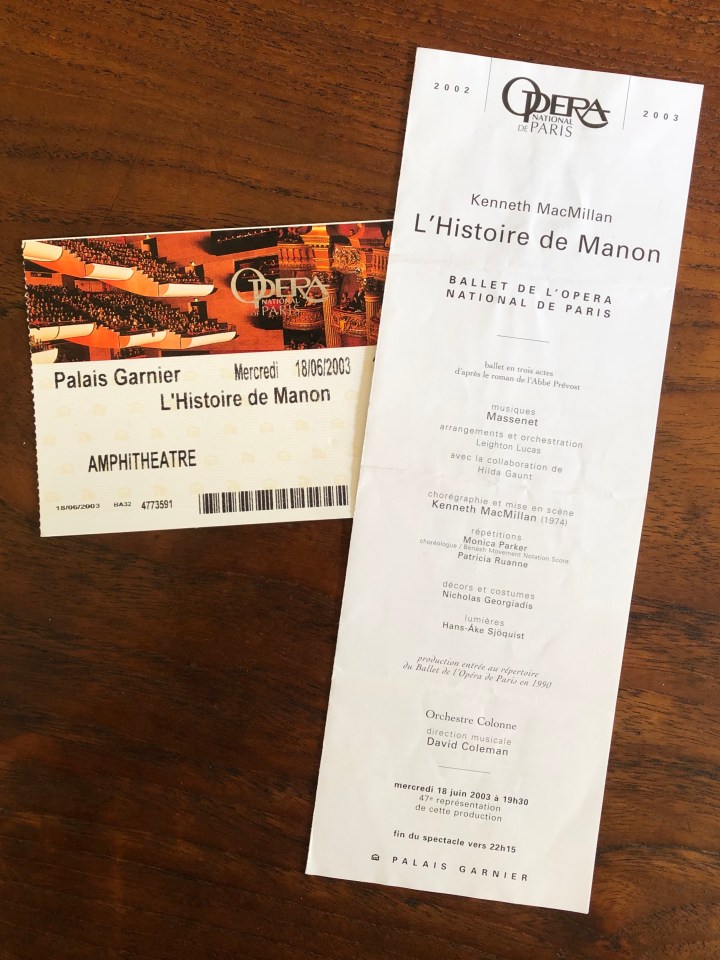

The first time I saw Manon was in 2003, in Paris, where it’s called L’Histoire de Manon. I was 17 and there with my parents, excited to be seeing the Paris Opéra Ballet. Our seats, obtained with the help of our hotel’s concierge, were in the second-to-last row of the Palais Garnier. These two things I remember vividly: that the seats behind us were filled, last minute, by a group of casually-dressed teenagers, which I found tremendously sophisticated; and the thrill of having stumbled across such a wonderful ballet. I had never seen anything like Manon. “That first pas de deux,” I kept gushing. For me, the ballet peaked early on. But I still thought it was fantastic.

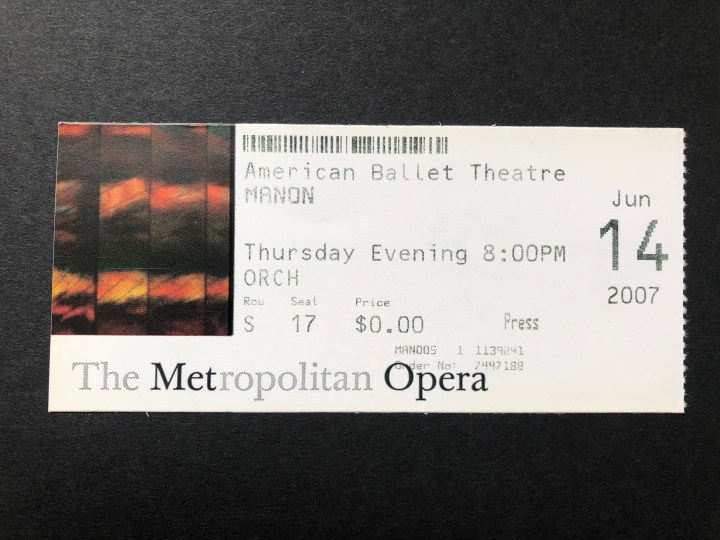

By summer of 2007, this single performance of Manon in Paris had become the stuff of legend in my mind. I spent the 2006-2007 school year as a visiting student at Barnard College, where I took a course in dance criticism taught by Mindy Aloff. She connected me with a writer and editor for ballet.co.uk. On this occasion, my assignment was to review Manon at American Ballet Theatre, led by an all-star cast of Alessandra Ferri, Roberto Bolle, Herman Cornejo, and Gillian Murphy. Ferri was retiring from ABT that summer, making this was one of her final performances with the company. If I didn’t have imposter syndrome in the moment, I have it now looking back: who was I to be reviewing Alessandra Ferri?! She, who I had watched so many times in the Balcony Scene from Romeo & Juliet on that VHS tape from the 1990s (that American Ballet Theatre Now: Variety and Virtuosity recording was a generation-defining video for many young dancers).

I arrived at the Met hyperventilating with excitement and armed with a press ticket in the orchestra—but carrying with me all the weight of that performance in Paris. I left exhilarated; it had surpassed all expectations. This became the new gold standard performance of Manon for me. I went home and submitted a glowing review to my editor.

Over the years, I saw the ballet several more times. In 2011, I saw it at the Royal Opera House in London with Laura Morera and Federico Bonelli. The Royal Ballet has screened it twice in cinemas, in 2014 with Marianela Nuñez and Federico Bonelli and in 2018 with Sarah Lamb and Vadim Muntagirov. Every time, I enjoyed the ballet, but I always thought, “Still not as good as Alessandra Ferri and Roberto Bolle in 2007!”

By summer of 2015, that performance of Manon at ABT had become the stuff of legend in my mind. Poor Paris! Supplanted. But Paris was looming large again. In the intervening years, I had discovered, and duly obsessed over the dancing of, Paris Opéra Ballet étoile Aurélie Dupont. When I heard that she was retiring, and that her official “adieux” would be in Manon, well—do I even need to tell you? Of course I had to go. Tickets had sold out immediately, but so great was the magnitude of Aurélie’s retirement that her farewell performance was being livestreamed in cinemas across Paris, and I managed to snag a cinema ticket before that, too, sold out. [I would like to pause for a moment, now, and ask my U.S. readers to picture this happening with a ballet performance here. What a problem to have!]

At the cinema, I ended up with a better view than I would have had at the opera house thanks to the film cameras. There was even a bonus interview with Aurélie, pre-recorded and screened at intermission and thankfully subtitled in English. I remember sitting there feeling so, so lucky, and not caring a jot that I wasn’t “seeing it live.” Because it was live, across the city. My favorite moments were those when the audience cheered so loudly at the end of a scene that the dancers had to play for time, the orchestra waiting for quiet. Even at the cinema, the excitement and enthusiasm were palpable. But was it better than 2007? Though I was loath to rank it above 2007, I was equally worried about giving it short shrift. I understood in the moment that what I was responding to was more than the performance. It was the whole experience. It was being in Paris, seeing something I really cared about and wanted to see, on a trip that was proving to be delightful, surrounded that evening by a bunch of strangers equally enamored of this artist and her career.

By summer of 2020, you will not be surprised to learn that when Facebook reminded me I had seen Aurélie Dupont’s farewell performance five full years ago, I was overcome with nostalgia. I started, and abandoned, a blog post about it. English National Ballet streamed Manon during lockdown; I turned it on in the middle of my favorite pas de deux.

Then, last week, I got an email from ABT. As a thank you for my donation, I would be receiving a link to a video. The video, from the archives, was of Manon, filmed in 2007 with Alessandra Ferri and Roberto Bolle. Yes. The very performance I reviewed 13 years ago. I was immediately all a-flutter—and grateful that I could still feel excitement. These months of “sheltering” have sapped my spirits, but here was proof that I was still capable of being excited, specifically about ballet.

I was also terrified. What if it didn’t live up to my recollection? Live performances, for the most part, remain only in memory. When the link arrived, I clicked with a mixture of nerves and anticipation.

It wasn’t the same.

Since 2007, I have seen Manon, in full or in part, in person or on screen (YouTube included) probably a dozen or more times. That same summer I saw Aurélie in Paris, someone uploaded the entire stream to YouTube; I think I watched Act I every day for a couple of weeks at least. And naturally I bought the DVD when it came out. I can play Aurélie Dupont back in my mind, not because she was better than Alessandra Ferri but because I have watched the recording of her so many times. (Incidentally, there are several different recordings of the ballet available for purchase. For me, it was about reliving what I had seen specifically.)

I let a few days pass and decided to watch it again. This time, without all the pressure, the magic was back. I could see how I’d gotten caught up in the performance, and why I’d written what I had in my review. And, finally, I understood that as in 2015, what I had glorified for so many years was more than the performance itself. Yes, it had been fantastic. But what made it stick with me was everything else: getting a press ticket, the great seat, writing one of my first reviews, the thrill of seeing those ballet stars up close. It was, essentially, a life event, and what I remember is the feeling, which was exhilaration. Which is what I felt the first time, sitting up at the top of the Palais Garnier with my parents. Which is what I felt watching again in 2015, aware of all these other Manons that had come before.

Getting to see this exact film was freeing, actually. There is room, in my memory, for all of these performances to have been great, to have been the best. They certainly were in the moment. And there is plenty of room for future performances, as yet unseen, to be the best, to be celebrated, and to become cherished memories, just like these.

Want to watch?

Here are Alessandra Ferri and Roberto Bolle dancing the first pas de deux that I love so much at Teatro degli Arcimboldi in 2004; this link includes the variation for Bolle as Des Grieux before the pas—that music!

Compare that to Aurélie Dupont and Roberto Bolle in the same pas de deux at her farewell performance at the Palais Garnier in 2015. Aurélie was supposed to perform with her frequent partner, Hervé Moreau, but he was injured at the last minute and Roberto Bolle replaced him.

The next pas de deux, the bedroom pas, is only a few minutes and a scene change later. Continuing with Aurélie Dupont and Roberto Bolle, here they are in the same performance in 2015.

Compare that to Marianela Nuñez and Federico Bonelli, also in the bedroom pas de deux, at The Royal Opera House in 2014.

Just to be well-rounded, here’s a clip of Manon’s variation from Act II. It’s her only variation in the entire ballet, which is mostly told through a series of pas de deux (or trois, or more) that show Manon in relation to the men in her life. This is Aurélie Dupont in 2015, but you can also watch Tamara Rojo in 2008 if you want to do another compare and contrast!

Finally, we have Sarah Lamb and Vadim Muntagirov in the final pas de deux at The Royal Opera House in 2019.

Now you’ve seen almost the entire ballet!

I have included my original review of the ABT performance here, as it can no longer be found on ballet.co.uk, where it was originally published.

American Ballet Theatre: Manon

June 2007

New York, Metropolitan Opera House

by Ellen Gaintner

The first time I saw Manon was in Paris, four years ago. My seat was in the second-to-last row of the Palais Garnier. I had never heard of Manon, but I was desperate to see the Paris Opera Ballet. I do not remember, sadly, who I was fortunate enough to see that night. But what I do remember is coming out of the first act dazed by the beauty of MacMillan’s sumptuous choreography. Neither the second or third acts lived up to the first for me. Until this performance by American Ballet Theatre, I had not seen the ballet again. The first pas de deux between Manon and Des Grieux had, however, remained in my memory as one of the most exquisite pieces of dancing I had ever seen. Needless to say, I was eager to refresh my memory and see it again.

It lived up to my recollection. In her final ABT performance of Manon, Alessandra Ferri, dancing with guest artist Roberto Bolle, had the audience on its feet, tossing bouquets as the curtain calls went on and on, even after the house lights had come up. What is it about Ferri? A young dancer sitting near me sighed, “Those feet!” Yes, yes. We all know about “those feet.” Possibly the most famous feet in the world. But there is so much more to her dancing than her arch. She makes a small rond de jambe en l’air into a work of art. When, in that long series of over-the-shoulder lifts in Act II where Manon is passed from man to man, she developpés her leg straight up into the air, it’s about how she unfolds her leg. It is indeed a gorgeous leg, finished with a perfectly pointed foot. What is so beautiful and exciting—yes, exciting—about it, though, is the way it is done. The care she takes, the deliberateness. That was what made the rond de jambe. And then, moments later, she can let herself be flung about or be caught up in a passionate embrace.

She is also an actress. Manon is not a particularly likable character. Fickle, weak, and easily tempted, it takes quite a lot of ability to make the audience not only feel for her, but also understand Des Grieux’s infatuation. I have read the Abbé Prévost’s novel. Des Grieux throws his own life—past, present, and future—away for her. His life revolves around her; without her love, he can barely justify his existence. The story is a real downer, and you come away from it feeling great pity for Des Grieux. The ballet is somehow even more moving, and makes Manon the object of pity and compassion. She is so young, so fresh in Act I, and by Act III she is on her knees, humbled before the Jailer, dead in Des Grieux’s arms.

That first pas de deux that I found so memorable—not in the bedroom but the one before, in the square—sets up the entire ballet. It begins with a solo for Des Grieux, his declaration of love. He is visibly cautious in this demonstration of his attraction. How will she respond? She is a lovely young girl, on her way to enter a convent. Appropriately for such a character, she is shy to begin with. She is not the engaging flirt she plays when she is with Monsieur G.M. Her entrance into the pas de deux with Des Grieux is timid, though it warms quickly, the movement becoming faster and more sweeping, the affection growing more ardent. Literally caught up in his arms, in a whirlwind of lifts and turns, Manon cannot resist Des Grieux’s earnest love. The whirlwind quality of their dancing returns again and again in their pas de deux. Manon dances differently with Des Grieux than she does with any other man in the ballet. She is closer to him, physically, and she moves with him, their bodies coming together and apart in constant motion, never lingering, because despite the lushness, there is a sweep, a swiftness, that reflects the intensity of their deep but tortured love for one another. When Manon dances with Des Grieux, she is flung about, lifted, and spun with an exhilarating abandon. When she dances with the other men, she is carried rather than lifted, supported rather than handled. Manon is far too spirited, however much she may like the finer things in life, to deny herself the excitement that accompanies Des Grieux’s love.

And who could resist anything offered by this tall, dark, handsome Italian? Bolle, a resident guest artist at La Scala Ballet, delivered an intense performance as the diligent student who becomes smitten with Manon. His great height—he towers a good head and a bit over Ferri, as well as everyone else—makes his partnering of Ferri deliciously smooth. It also creates a paradox. He is the tallest man on the stage, and yet he is consistently beaten in both brute force and will power by men smaller than himself, in particular Herman Cornejo as Lescaut, Manon’s conniving, greedy brother. Lescaut spends the final moments of Act I pushing Des Grieux around, even knocking him to the floor, and the curtain falls as Lescaut twists Des Grieux’s arm behind his back. That Cornejo can physically dominate the scenes he shares with Bolle is due to the energy with which he attacks the role, to his superb jump (he tossed off the Act I solo with finesse), and to his wit (he and Gillian Murphy found unsuspected depths of humor in this tragic tale in their Act II drunken pas de deux). None of which is to say that he upstaged Bolle. They are very different dancers, and they complemented each other nicely.

I could go on and on. I could talk about how MacMillan always seems to choose complicated stories, such as Manon or Mayerling. I could talk about how the pas de trois in Act I can be interpreted literally as Lescaut and G.M. manipulating Manon. I could talk about how important the use of gaze is, and how Ferri uses it so well, something I could see very clearly from the Orchestra but would not have picked up from the Family Circle. I could talk about how I don’t like the courtesans’ wigs, and I could mention that the set change in Act III from the port to the jailer’s room was embarrassingly loud and excessively long, with no music to cover it. I could also mention that the thick ropes that create the swamp make it very difficult to see the dancers behind them, which is perhaps the goal but again is inconsiderate of people sitting further away. And I could just keeping talking about Ferri, and her interpretation of the character, and the fluidity of her dancing, and those absolutely undeniably voluptuously arched feet.